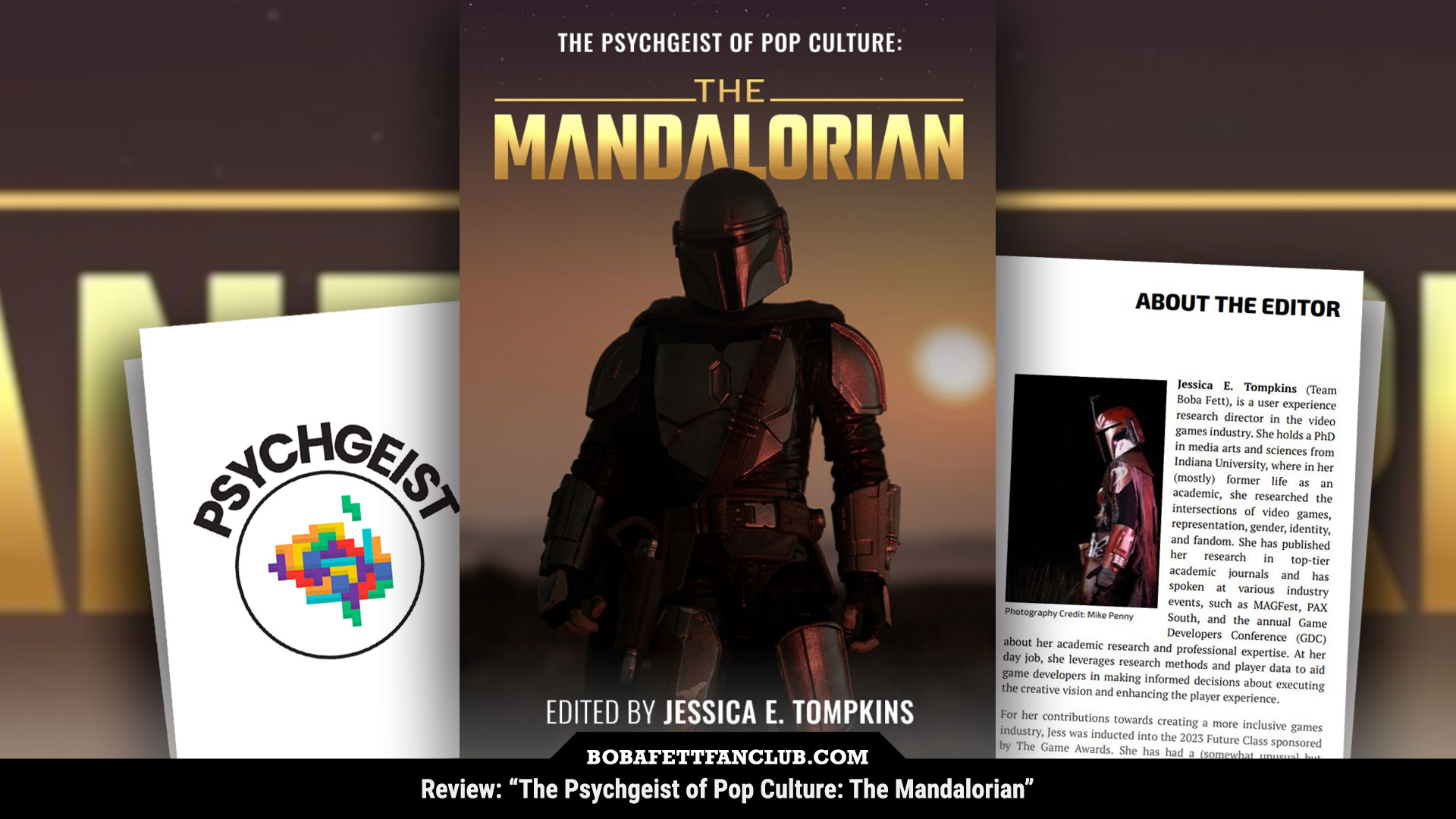

Review: "The Psychgeist of Pop Culture: The Mandalorian"

I can read this book warm, (dramatic pause) … or I can read this book cold.

What do I mean? Well, “The Psychgeist of Pop Culture: The Mandalorian” — a collection of essays written by academics and scholars around the world, edited by Dr. Jessica E. Tompkins (BFFC member #16), with series editor Dr. Rachel Kowert — is sure to be enjoyed by many Star Wars fans, but it is unlikely that all will agree with everything presented in the book… but that’s the point. We all have our own thoughts and beliefs, so while we all watch the same show, for each of us it’s unique, because we are likely to have different interpretations That is the charm of a collection of Star Wars essays by different, diverse writers. It is such ‘food for thought’ it might as well be an all-you-can eat buffet – but, can you stomach the food? This review will go through a quick rundown of the essays featured in “The Psychgeist of Pop Culture: The Mandalorian” that deal in the psychology of the characters and narrative themes found in “The Mandalorian” and “The Book of Boba Fett” from different perspectives, angles, and fields of study.

1. “Mando with No Name: The Mandalorian as nostalgic Western cinema” (Nicholas David Bowman, PhD. and Koji Yoshimura, PhD.)

This first essay reads like 2-in-1, with the first half focusing on the history of Western cinema and how its legacy inspired Star Wars’ space western elements, in particular Boba Fett and Din Djarin. Both characters were inspired by the iconic “Man with No Name,” a poncho wearing, stoic gunslinger-with-spurs antihero that Clint Eastwood portrayed in the “Dollars Trilogy” Spaghetti Westerns. Mando with No Name features a thoughtful analysis on the most-Western inspired episodes of The Mandalorian, such as “The Gunslinger” and “The Marshal” featuring Cobb Vanth. The writers also speak of Cad Bane, perhaps the most-Western influenced character of “The Book of Boba Fett” and compares Bane to a character named Liberty Valance, an evildoer from a Western film who arguably inspired Bane’s appearance. However, the writers overlooked mentioning actor Lee Van Cleef, who portrayed an evil henchman in the film “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence.” Van Cleef was inspiration for Cad Bane’s design. Omitting this detail was a bit disappointing because we know from the behind-the-scenes development that George Lucas insisted on Bane taking inspiration from Lee Van Cleef (as opposed to a more armored design like Durge, another bounty hunter character to whom Cad Bane was spun off from). Overall, this essay provides a good argument on nostalgia’s role in marketing The Mandalorian, but I argue it was not just the nostalgic yearn for more content tied to Boba Fett’s legacy and Western media tropes, but also nostalgia for Attack of the Clones’ Jango Fett too(who was created out of nostalgia for the pre-clone version of Boba Fett, much like Din Djarin was). Nostalgia is a hard thing to measure by any metric, as fans were attracted to The Mandalorian without knowledge of the Fett’s or Western film history. How much nostalgia plays into The Mandalorian’s success has always been a moot point, in my opinion. It is a factor, but to what degree? It’s hard to tell.

2. “Like Father, Like Clone? Boba Fett’s Nature and Nurture” (Jessica E. Tompkins, Ph.D.)

This essay gets in depth with Boba Fett, even providing an overview of his history, including some great references to the Boba Fett of the EU (e.g., being a Journeyman Protector, gladly hunting a Spice dealer for Jabba) prior to him being retconned as a clone. For those to truly understand Boba Fett and his legacy, one must understand his history, because by understanding that, you’d know there were already multiple versions of Boba Fett way before “The Book of Boba Fett” aired. Critics who didn’t know this made it seem like the character had changed for the first time in his show. But this essay understands that and provides a thoughtful analysis of his character, like the symbolism of Jango Fett not physically appearing in Boba Fett’s flashbacks about Kamino and Geonosis, the spiritual rebirth he went through after emerging from the womb-like hell of the Sarlacc’s insides, and the symbolism of snapping the wortwood tree’s branch and severing his bounty hunter ties for good.. This chapters also explores his bond with Fennec, how it differs from the relationship Jango had with Zam Wesell (of Attack of the Clones), whom Jango was quick to kill in order to protect himself. The role of Cad Bane in his development is similarly explored. The author argues thatCad Bane is symbolic of Boba Fett’s former ‘predisposed’ nature (due to genetic inheritance) who put ruthlessness and self-interest above community and compassion. Based off the arguments presented one could additionally say that Boba Fett killed not just a version of himself by killing Bane, but a version of his father, Jango. Even the sad way Boba seems to walk away from Bane’s dying/dead body signifies a deep loss, rather than a victory against a rival old enough to be his uncle. Overall, this is a good study on how genetics and environment play into how Boba Fett is characterized, and how he has evolved, while challenging the notion of him being soft.

3. “Wonderful (Non-)Human Beings: Seeing Human in a Galaxy Far, Far Away” (Kevin Koban, PhD)

This essay delves into Anthropomorphism in The Mandalorian, categorizing them in several groups: The Near-Humans, Zoomorphs, Enigmas andDroids. This is an intriguing analysis on the differences between alien species that are sometimes very human-like but sometimes not at all. The near-humans are so human-like that they might as well be seen that way by the audience, such as the Tortuga Ahsoka, the Twi’Lek characters (which there are several of within the Mandoverse), the leathery skinned Weequays, or the blue-faced Thrawn; they are alien species that are human enough to be seen as familiar to the audience. Then there are enigmatic species, such as the Jawas, Tuskens, and the mysterious “Frog” people who speak enigmatic languages. The author also discusses the Zoomorphic type species like Grogu, the Ugnaughts and Mon Cala species who do not resemble humans but have some animalistic traits.. Lastly, this essay goes into the Mechanical entities, the Droids, such as R2/R5/Chopper, IG droids, C-3PO and many others, making mention of The Mandalorian Season 3’s sixth episode featuring Existential droids. The author also explores the Star Wars vision in general, how it mixes serial storytelling and Sci-Fi with the use of anthropomorphic characters, and how the Mandoverse pays tribute to that vision. This chapter is more of a cool read, since one of the first things people observe of Star Wars is the Anthropomorphism in varying forms. It is arguably one of the aspects that draws people into Star Wars, although the series ‘Andor’ also proves that when it’s done in a more minimal way it can be just as effective as when it is done in excess.

4. “The Psychology of Ownership: Boba Fett’s Armor and the Darksaber as Cultural Heritage” (Stephanie Orme, PhD)

This chapter draws an interesting parallel about ownership using Boba Fett’s armor and the Darksaber. Both have their own history, have had several owners, and both resonate with the fans of Star Wars for their significance, albeit in different ways. However, one criticism I had was about the idea that Cobb Vanth felt he had the right to wear Mandalorian armor. This is because he was quick to understand, without being told, that a real Mando would not be happy with him wearing it. To me, while watching the series, it seemed Vanth’s need to protect his territory and people is what made him feel he had the right to keep it, rather than a case of valid ownership. His forthright acknowledgement that he got it from Jawas is basically admitting that the armor was stolen goods. Also, the writer mentions that Din Djarin agreed to return Boba Fett’s armor. –While it is true that Din did acknowledge Boba’s ownership of the armor (after proving his father Jango was a Mandalorian foundling), once he lost his Razor Crest ship on Tython, Din was no longer in any position of telling Boba Fett what he could or couldn’t wear(seeing as Boba was his only way off that planet and Boba already secured his armor). In my opinion, the fact that Boba went out of his way to assure Din about the authenticity of his ownership shows he respected Din’s views on Mando armor ownership, even if he didn’t like how Din had declined to give it back when Boba demanded it in a hostile manner.

Otherwise, this essay does a good job in analyzing both the armor and the Darksaber. Here, the author presents the background and history of the Darksaber, where it came from (Tarre Vizsla) and those who owned it (Pre Vizsla, Bo-Katan, Moff Gideon). Fans of The Clone Wars and Rebels will appreciate the level of depth regarding the Darksaber’s history and how Bo-Katan ended up with the Darksaber to begin with (through Sabine Wren, but there’s more to the story, of course).Fans of Season 3 of The Mandalorian will likewise appreciate this essay, as S3 went into the later history of the Darksaber, how it ended up with Moff Gideon for a time, and why Bo-Katan felt too much shame to accept the Darksaber from Din Djarin after he defeated Gideon.

5. “Is this The Way? The Mandalorian’s Moral Journey” (Rowan Daneels, Ph.D.)

This essay goes into the subject morality in The Mandalorian using Moral Foundations Theory (MFT), applying these sets foundations to the Mandalorian Creed of caring for foundlings and showing loyalty and solidarity to other Mandalorians. Now, this essay I found interesting because I never really thought about the morals of the Creed;I just saw the Creed more as guidelines to live by that serve to create future generations of Mandalorians loyal to the ancient ways.As such, I previously did not consider thinking about the bounty hunting profession as something contradictory to the Mandalorian Creed. Bounty hunters, being free to select the missions they pursued could simply avoid missions that they thought would be in conflict with their morals. The problem is that sometimes missions are not what they are expected to be – like taking a job from a seemingly harmless “Imperial warlord” to hunt for a “50 year old” bounty to gain beskar that was stolen from Mandalore. The morality of bounty hunting aside, this essay shows Din Djarin’s moral journey with Grogu and how it ended up transcending the Mandalorian Creed, in a way that was problematic to his version of morality. This chapter demonstrates how he is able to reconcile things in the end, redeeming himself as a (Children of the Watch) Mandalorian and as a father to Grogu who becomes an official Mandalorian foundling by the end of Season 3, hinting that Grogu will develop the same Mandalorian morals and values as his father over time.

6. “He’s one of Them: Social Identity and the Mandalorian” (James D. Ivory, Michael Senters, Virginia Tech)

This is an enjoyable essay about social identity applied to The Mandalorian, including some mentions to themes and characters beyond the series. For example, there is a great reference to the series Rebels involving the Mandalorian-Jedi Sabine Wren and Jedi Ezra Bridger that gets tied into the idea of Mandalorian armor as a condensation symbol.This chapter demonstrates how Mandalorian armor is more than just armor to the owner, because it can signify emotions, memories, family as well as Mandalorian history. Furthermore, the author makes a parallel between the Stormtroopers of the Empire, who are victims of de-individuation(lacking individuality) and the Mandalorian people, who reject de-individuation, and embrace individuality as evident by the different armor designs. However, despite that, Mandalorian factions still bickered and fought on issues of identity, especially after the Great Purge, as noted by the writer, which is some spot-on analysis. An interesting read.

7. “A clan of two: Attachment & Connection” (Kelly E. Pelzel, PhD and Brugundy J. Johnson, DO)

This chapter discusses Attachment Theory as applied the attachment needs of both Din Djarin and Grogu. It goes into depth about how Din Djarin, despite having a traumatic past, connects with Grogu and secures a bond as his caretaker. This offers an interesting analysis of the caretaker role as applied to Djarin, and shows the influence that his allies had on his parenting. For examplePeli Motto and Greef Karga played a role in leaning Din Djarin toward being a parent, pushing him towards that direction at times, whereas Ahsoka Tano and The Armorer offered Grogu a pathway to be reunited with a Jedi that could train him, as opposed to pushing Din to fully embrace his role as the father of Grogu. This is not a slight on either Ahsoka or The Armorer, of course, they were simply leaving it to Din to make those decisions even if Din was indecisive beyond his need to protect “the child” (as he used to affectionately call Grogu). Peli Motto, in contrast, even considered Grogu as Din’s son. For example, she presented Din with the Naboo starfighter that was customized for Din and Grogu in mind. This essay leads up the moment of the secure attachment being solidified (in season two) when Din Djarin unmasks for Grogu before he sends him off to train with Luke Skywalker as his first student. The authors analyze the moment through attachment theory, arguing that Din says goodbye to Grogu using facial emotions and physical touch that were previously missing from their father-son relationship because of his adherence to the Creed. A Good read about the Mudhorn Clan.

8. “Wherever I go, he goes: Fatherhood and male emotion” (Keely Diebold and Meghan Sanders, Ph.D.)

This chapter contrasts Din Djarin and Anakin Skywalker, so fans of the Prequel Trilogy (“The Phantom Menace,” “Attack of the Clones,” and “Revenge of the Sith”) will want to read this one. I found this fascinating because when I watched Attack of the Clones I could not help but compare young Boba Fett with the young Anakin Skywalker and the similar dark trajectories that followed after they lost the family they were attached to.Yet, I never thought to do the same with Din and Anakin, who really do come off as opposites when it comes to male emotion.

This essay explores their traumatic pasts as well as Djarin’s shift from having an avoidant and insecure attachment style (attributed to being raised by authoritarian Mandalorians and associating with underworld contacts like Greef Karga), to possessing a secure attachment style, as a solitary figure with a traumatic past who is able to make a secure bond with a loved one like Grogu. Comparatively, Anakin Skywalker loses Qui-Gon so fast, followed by his mother Schmi on Tatooine, that he developed an anxious, ambivalent attachment style that led to his downfall. Not only because Palpatine had manipulated him, but because Anakin was skeptical of the Jedi way that he perceived as an obstacle to protecting his loved ones, leading to his anger and ambivalence.

I agreed with this essay’s arguments, although it could have gone more in depth on the history of hyper-masculinity in cinema in relation to Star Wars.There’s no mention of George Lucas wanting to make a Flash Gordon serial prior to creating Star Wars. The character Flash Gordon (dubbed the “King of the Impossible”) is, from what I understand, an athletic, intelligent, and brave Sci-Fi hero who would go on adventures on different planets with other characters. Sowhen George Lucas made Star Wars, his male heroes like Luke Skywalker and Han Solo similarly shared those traits. The essay makes a thoughtful point regardless.

9. “We’re All Equal Here: Women of the Mandalorian” (Gina Marcello, Ph.D.)

This essay offers a feminist perspective that analyzes the main female characters from “The Mandalorian” and “The Book of Boba Fett” such as Bo-Katan Kryze, Fennec Shand, The Armorer, and Cara Dune. It’s unfortunate this essay does not get into any other female characters (bad news for Frog Lady fans) but that’s okay, the point was to look at the most popular characters. The author argues these women are portrayed with masculine traits, but yet unlike the male heroes, they lack the moral agency that characters like Din Djarin have. Additionally, the author notes that these heroines lack a feminine voice, with the exception of season three of The Mandalorian where both Bo-Katan and the Armorer enact moral agency and a feminine voice to bridge divides in the Mandalorian community. The essay also argues that Jon Favreau (being influenced by Western cinema that portrayed women as either damsels in distress of femme fatales) struggled to do justice to characters like The Armorer, Bo-Katan, and Fennec Shand until they underwent moral transformations post-season two, and that Cara Dune remained the one female character (with masculine traits) that was portrayed with moral agency from the start and did not need to undergo a moral transformation.(Although, it should be noted that being from Alderaan, , the implication might be that her moral transformation began during the events of A New Hope, and that’s what led her to fight for a greater cause in the war). The essay also considers that season three would likely have been written differently had Cara Dune’s actress not been removed from the show, and makes a case for the need for a character like her to return. On Fennec Shand, she is described as a “right hand man” to Boba Fett, but this felt a bit like a cheap shot, since being a right-hand man/woman is honorable; it implies skill, strength, loyalty, and trust. Considering Boba Fett saved her from certain death did not turn her into the law (as there was a bounty on her), offered her freedom after she helped him get his ship back, and then offered her equal status as his partner, I think they have a great relationship going on. Fennec has shown some softer moments; for example, hanging with Cara Dune in ‘The Believer’ episode, bonding with Drash after saving her life in TBOBF finale, so I felt this essay was a bit harsh in the description of Fennec. However, the analysis of The Armorer, Bo-Katan and Cara Dune make for a good read.

10. “Scars on the Inside: Trauma and Recovery” (Blake Pellman, PhD)

‘Scars on the Inside’ might have been my favorite chapter of this book. It is very well written, and intense as it goes in depth with trauma, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in “The Mandalorian” and “The Book of Boba Fett.” It explores the traumatic events of Din Djarin, Boba Fett, and Grogu, who’s PTSD is most exemplified in season three’s “The Foundling” . This essay details the Neurobiology of Stress, Fear, and Memory, and the Social Impact of trauma for these characters. There is some fascinating insight on why Din Djarin, in the first chapter of The Mandalorian, decided to Grogu from IG-11 out of fear stemming from his own childhood trauma. It’s an interesting notion that his attack on IG-11 was the result of a PTSD trigger, as Din was once a child hunted by droids before being saved by the Mandalorians, leading to his intense droid phobia. The essay also discusses trauma and recovery in “The Book of Boba Fett,” the healing power of relationships and community within the context of post-Sarlacc Boba Fett and the Tusken Tribe that not only saved him from dying, but helped him resolve the trauma he carried for so long after witnessing Jango Fett’s beheading in battle with the Jedi. I would have liked a bit more detail on Boba Fett, but it’s probably better to present these arguments concisely.

11. “These people lay ancestral claim to the Dune Sea: Racialization & the Problematic Portrayal of the Tusken Peoples” (Carlina de la Cova, PhD)

The Tusken Raiders … also known as the “Sand People.” Yeah, the portrayal of the Tuskens was problematic, but how and why? This chapter goes into all of that. The author discusses how Tuksens were racialized caricatures rooted in Western and Scientific Racism (a form of bad science that negatively impacted non-white people) pioneered by European White Scientists (of the past),For this reason, Tusken portrayals became problematic as Star Wars grew in popularity overtime. Tuskens, being the native and indigenous people of Tatooine were originally presented as savage, unintelligent, barbaric beings, but the more we learn about them,we came to understand that were not uncivilized, and in fact have their own complex culture, traditions and values (even though that includes crossing lines, like the way they kidnapped Shmi Skywalker, which led Anakin to destroy an entire Tusken tribe, hinting Anakin may have grown up believing them to be subhuman because he showed no mercy in his slaughter of innocent Tusken children). However, this essay notes many in the Star Wars universe hold a negative view of Tuskens, like Toro Calican in The Mandalorian who mentions that Tatooine locals saw Tuskens as filth. This aligns with the original Star Wars film where both “Ben” Kenobi and Luke look at them as mindless monsters. The author even mentions that neither Obi-Wan nor Luke attempted to learn the Tusken language as the Mandalorian Din Djarin did, but this opens up a problem I have with the show; how did Din Djarin learn to speak the enigmatic Tusken language? Even Boba Fett, who lived with Tuskens, did not learn their verbal language (opting for Tusken sign language).Din Djarin used sign language in his first interaction with Tuskens in ‘The Gunslinger’. It’s not until season two that Din suddenly shows he can speak Tusken, too. I found this incredibly odd. Did The Mandalorians who raised him teach him? Did he learn in between season one and two? Honestly, I’d love an answer to that – but now I am way off my review.

One criticism I did have was the idea of “The Book of Boba Fett” being a “White Savior Story” in regards to the whole sequence where Boba and the Tuskens stop the Pyke’s Train that smuggled Spice and shot at Tuskens indiscriminately. Sure, they couldn’t stop the train without Boba acquiring the technology they needed (speeder bikes), as well as him teaching them how to operate thev speeder, but the Tuskens are portrayed as quick learners. And really, Boba’s plan would have failed were it not for one particular Tusken who killed as many Pykes as he did and opened up a path for him to advance to the front of the train. I think a much better example of a “White Savior Story” would have been Season two’s opening chapter where a Greater Krayt Dragon is too much for the Tuskens that they need assistance from those they perceive as colonists (Cobb Vanth and his people) as well as Mandalorian Din Djarin, who ends up being their ‘knight in shining armor’ as he alone (and a Bantha armed with explosives) takes down the Greater Krayt Dragon. Even though the Tuskens have far more experience against such creatures than someone who isn’t a local, they needed Din in order to kill the creature. I think that fits the description better of a “White Savior Story” than “The Book of Boba Fett” where Jon Favreau included better writing and highlighted what the Tuskens were capable of, rather than their ineffective and expendable portrayal from “The Marshal.” But that’s the kind of food for thought this essay offers.

12. “Memories of Mandalore: Memory and Recollection” (Michael J. Serra, Dept. of Psych. Sciences, Texas Tech U.)

This final essay goes into flashbacks. Flashbacks of all kind, from the traditional flashbacks of Rogue One and Andor, to the trauma-based flashbacks of The Mandalorian, the flash-forwards of The Sequel Trilogy, the Force-induced flashbacks of Grogu and Ahsoka, the amnesia-related flashbacks in the case of Darth Revan, the explanatory flashbacks (Cobb Vanth’s story of how he got Boba Fett’s armor, and Kuiil’s IG-11 story) and of course, the Boba Fett bacta-pod flashbacks. Boba’s flashbacks served two purposes; as a plot device to explain the unexplained gaps in his history that tied to his appearance in The Mandalorian, and also as a way to explain how and why Boba Fett feels the ways he does in the present timeline of the show. This essay also makes mention that George Lucas’ Star Wars (the first-six live-action films) did not use flashbacks, and had more of a serialized sequential storytelling approach as events outside of what was shown were left to the imagination (or mentioned in the opening text crawl of the film).

When Disney acquired Star Wars sequential storytelling ended and flashbacks have been the norm ever since in major Star Wars media projects, which then leads to the question, “Does Star Wars need flashbacks?” That’s a great Star Wars question indeed, and one the writer answers eloquently.

I will close up by saying that this book is not just for the “Mandoverse” fans, but for all fans of Star Wars, and not just one type of fan, but for all fans from all backgrounds and points of view. People do not simply become Star Wars fans for silly reasons, as some may think. They take it seriously because it is rich in history; it has a legacy and a story with limitless potential in the right hands. These are fun stories made by intelligent people, for other intelligent people who want fun stories. This book shows that intelligent side that is often overshadowed by negative talk of a toxic Star Wars community. A book like this a good reminder that Star Wars is not meant for antagonistic internet trolls; that many smart people are investing their time analyzing it’s characters and themes as if they were in Star Wars College, studying the Mandalorian and Jedi Sciences. So I highly recommend this book, but if you aren’t interested in psychoanalyzing Star Wars and would rather see it as mindless entertainment, maybe this won’t be for you. In sum, I would say this book is up the alley of most Star Wars fans, as well as something people into pop culture psychology would similarly enjoy.

Rating

More Info

- Title: “The Psychgeist of Pop Culture: The Mandalorian”

- Formats: Paperback, ePub, Downloadable PDF

- Language: English

- Website: https://press.etc.cmu.edu/books/psychgeist-pop-culture/mandalorian

- Price: PDF: Free; Ebook: USD 3.99 USD; Paperback: USD 18.00

- Synopsis: The Psychgeist of Pop Culture: The Mandalorian is an interpretative collection of essays that unpack the narrative themes and characters belonging to the beloved Disney+ series, offering new insights and psychological perspectives about characters like Din Djarin, Grogu, Boba Fett, and many more. Using examples from the series, readers will walk away with a deeper understanding of psychological frameworks that may shape ourselves as well as beings in a galaxy far, far away.

More from This Author

The Animated Legacy of Boba Fett – Part 1

The Animated Legacy of Boba Fett – Part 1

The Fetts and the Droids: Artificial Intelligence in Fett Lore

The Fetts and the Droids: Artificial Intelligence in Fett Lore

How Jango Fett's Motivation Evolved from George Lucas to "Legends" to Present

How Jango Fett's Motivation Evolved from George Lucas to "Legends" to Present

How Boba Fett’s Backstory Evolved from George Lucas to “Legends” to Present

How Boba Fett’s Backstory Evolved from George Lucas to “Legends” to Present

Comments